Performance: when algorithmics meets mathematics

In this post, I talk about performance through an efficient algorithm I developed for finding closest points on a map. This algorithm uses both concepts from mathematics and algorithmics.

Problem to solve

This problem comes from a recent question on StackOverflow.

I have two matrices, one is 200K rows long, the other is 20K. For each row (which is a point) in the first matrix, I am trying to find which row (also a point) in the second matrix is closest to the point in the first matrix. This is the first method that I tried on a sample dataset:

# Test dataset: longitude and latitude

pixels.latlon <- cbind(runif(200000, min = -180, max = -120),

runif(200000, min = 50, max = 85))

grwl.latlon <- cbind(runif(20000, min = -180, max = -120),

runif(20000, min = 50, max = 85))

# Calculate the distance matrix

library(geosphere)

dist.matrix <- distm(pixels.latlon, grwl.latlon, fun = distHaversine)

# Pick out the indices of the minimum distance

rnum <- apply(dist.matrix, 1, which.min)At first, this problem was a memory problem because dist.matrix would take 30GB.

A simple solution to overcome this memory problem has been proposed:

library(geosphere)

rnum <- apply(pixels.latlon, 1, function(x) {

dm <- distm(x, grwl.latlon, fun = distHaversine)

which.min(dm)

})Yet, a second problem remains, this solution would take 30-40 min to run.

First idea of improvement

In the same spirit as with this case study in book Advanced R, let us see the source code of the distHaversine function and see if we can adapt it for our particular problem.

library(geosphere)

distHaversine## function (p1, p2, r = 6378137)

## {

## toRad <- pi/180

## p1 <- .pointsToMatrix(p1) * toRad

## if (missing(p2)) {

## p2 <- p1[-1, ]

## p1 <- p1[-nrow(p1), ]

## }

## else {

## p2 <- .pointsToMatrix(p2) * toRad

## }

## p = cbind(p1[, 1], p1[, 2], p2[, 1], p2[, 2], as.vector(r))

## dLat <- p[, 4] - p[, 2]

## dLon <- p[, 3] - p[, 1]

## a <- sin(dLat/2) * sin(dLat/2) + cos(p[, 2]) * cos(p[, 4]) *

## sin(dLon/2) * sin(dLon/2)

## a <- pmin(a, 1)

## dist <- 2 * atan2(sqrt(a), sqrt(1 - a)) * p[, 5]

## return(as.vector(dist))

## }

## <bytecode: 0x71c0490>

## <environment: namespace:geosphere>So, what this code does:

.pointsToMatrixverifies the format of the points to make sure that it is a two-column matrix with the longitude and latitude. Our data is already in this format, we don’t need this here.it converts from degrees to radians by multiplying by

pi / 180.it computes some intermediate value

a.it computes the great-circle distance based on

a.

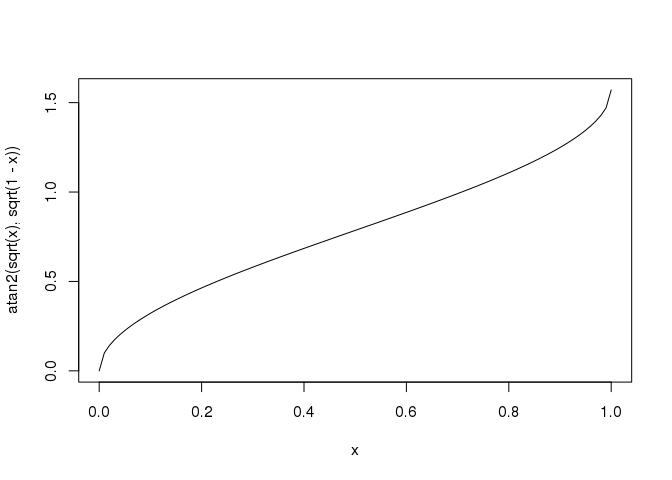

Knowing that latitude values are between -90° and 90°, you can show that the values of a are between 0 and 1. For these values, dist(a) is in an increasing function of a:

curve(atan2(sqrt(x), sqrt(1 - x)), from = 0, to = 1)

So, in fact, to find the minimum distance, you just need to find the minimum a.

# p1 is just one point and p2 is a two-column matrix of points

haversine2 <- function(p1, p2) {

toRad <- pi / 180

p1 <- p1 * toRad

p2 <- p2 * toRad

dLat <- p2[, 2] - p1[2]

dLon <- p2[, 1] - p1[1]

sin(dLat / 2)^2 + cos(p1[2]) * cos(p2[, 2]) * sin(dLon / 2)^2

}# Test dataset (use smaller size for now)

N <- 200

pixels.latlon <- cbind(runif(N, min = -180, max = -120),

runif(N, min = 50, max = 85))

grwl.latlon <- cbind(runif(20000, min = -180, max = -120),

runif(20000, min = 50, max = 85))

system.time({

rnum <- apply(pixels.latlon, 1, function(x) {

dm <- distm(x, grwl.latlon, fun = distHaversine)

which.min(dm)

})

})## user system elapsed

## 1.852 0.559 2.408system.time({

rnum2 <- apply(pixels.latlon, 1, function(x) {

a <- haversine2(x, grwl.latlon)

which.min(a)

})

})## user system elapsed

## 0.380 0.001 0.383all.equal(rnum2, rnum)## [1] TRUESo, here we get a solution that is 4-5 times as fast because we restricted the source code to our special use case. Still, this is not fast enough in my opinion.

Second idea of improvement

Do you really have to compute distances between all points? For example, if two points are on very different latitudes, does it mean that they are very far from each other?

In a <- sin(dLat / 2)^2 + cos(p1[2]) * cos(p2[, 2]) * sin(dLon / 2)^2, you have a sum of two positive terms. You can deduce that a is always superior to sin(dLat / 2)^2, which is equivalent to 2 * asin(sqrt(a)) is always superior to dLat.

In other terms, for a given point in your matrix, if you have already computed one a0 corresponding to one point in the second matrix, a new point could have its a inferior to a0 only if dLat is inferior to 2 * asin(sqrt(a0)).

So, using a sorted list of all latitudes and with good starting values for a0, you can quickly discard lots of points as being the closest one, just by considering their latitudes. Implementing this idea in R(cpp):

#include <Rcpp.h>

using namespace Rcpp;

double compute_a(double lat1, double long1, double lat2, double long2) {

double sin_dLat = ::sin((lat2 - lat1) / 2);

double sin_dLon = ::sin((long2 - long1) / 2);

return sin_dLat * sin_dLat + ::cos(lat1) * ::cos(lat2) * sin_dLon * sin_dLon;

}

int find_min(double lat1, double long1,

const NumericVector& lat2,

const NumericVector& long2,

int current0) {

int m = lat2.size();

double lat_k, lat_min, lat_max, a, a0;

int k, current = current0;

a0 = compute_a(lat1, long1, lat2[current], long2[current]);

// Search before current0

lat_min = lat1 - 2 * ::asin(::sqrt(a0));

for (k = current0 - 1; k >= 0; k--) {

lat_k = lat2[k];

if (lat_k > lat_min) {

a = compute_a(lat1, long1, lat_k, long2[k]);

if (a < a0) {

a0 = a;

current = k;

lat_min = lat1 - 2 * ::asin(::sqrt(a0));

}

} else {

// No need to search further

break;

}

}

// Search after current0

lat_max = lat1 + 2 * ::asin(::sqrt(a0));

for (k = current0 + 1; k < m; k++) {

lat_k = lat2[k];

if (lat_k < lat_max) {

a = compute_a(lat1, long1, lat_k, long2[k]);

if (a < a0) {

a0 = a;

current = k;

lat_max = lat1 + 2 * ::asin(::sqrt(a0));

}

} else {

// No need to search further

break;

}

}

return current;

}

// [[Rcpp::export]]

IntegerVector find_closest_point(const NumericVector& lat1,

const NumericVector& long1,

const NumericVector& lat2,

const NumericVector& long2) {

int n = lat1.size();

IntegerVector res(n);

int current = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

res[i] = current = find_min(lat1[i], long1[i], lat2, long2, current);

}

return res; // need +1

}find_closest <- function(lat1, long1, lat2, long2) {

toRad <- pi / 180

lat1 <- lat1 * toRad

long1 <- long1 * toRad

lat2 <- lat2 * toRad

long2 <- long2 * toRad

ord1 <- order(lat1)

rank1 <- match(seq_along(lat1), ord1)

ord2 <- order(lat2)

ind <- find_closest_point(lat1[ord1], long1[ord1], lat2[ord2], long2[ord2])

ord2[ind + 1][rank1]

}system.time(

rnum3 <- find_closest(pixels.latlon[, 2], pixels.latlon[, 1],

grwl.latlon[, 2], grwl.latlon[, 1])

)## user system elapsed

## 0.007 0.000 0.007all.equal(rnum3, rnum)## [1] TRUEThis is so much faster, because for one point in the first matrix, you just check only a small subset of the points in the second matrix. This solution takes 0.5 sec for N = 2e4 and 4.2 sec for N = 2e5.

4 seconds instead of 30-40 min!

Mission accomplished.

Conclusion

Knowing some maths and some algorithmics can be useful if you are interested in performance.